What’s this about?

I was a weird eighth grader to say the least. One of the odd questions I asked my teacher was, “Why do we use and in ?” Well, I’m sure I didn’t say that exactly, but you get the idea. Since eighth grade, I’ve kept learning more and more symbols every day, and by now my head is full of s, s, and s, and I demand an explanation for why! So that is what I am writing about today.

Really, this post isn’t fact. No one truly knows about these origins, but I’ll write out a few possibilities I found through my searching.

I think it’s pretty important to keep in mind, I’m an American. Now what does that have to do with this? Apparently, other countries use equations like instead. So why does America use and ? The explanation I’ve heard for is that it’s a translation of the French “monter” meaning “to climb” or “to go up”. And I’ve seen a lot of people say stands for “begin” but both of these explanations seem plausible at best.

Monte!

Monte!

Vertex form! Doesn’t this bring back sweeet memories from before conic sections!

- : This isn’t hard to explain. probably stands for amplitude.

- : There’s much more debate around this one. Some people vehemently argue that it stands for “horizontal”, while others say it stands for “hinge”.

- : Kertical? Some say this stands for “kardo”, a Greek word which transitively translates to “tendon”, something that helps parts of the body hinge vertically.

Some claim that and were just logical choices, considering almost all other letters were used, but I find this explanation just as unlikely as the one above.

Creakkkkk

Creakkkkk

I’ve been using and throughout this post, but never really questioned why? Why ? Why ?

The first theory I stumbled across for was a Spanish translation of the Arabic word for “something”, and was just the logical next value, but this doesn’t make much sense.

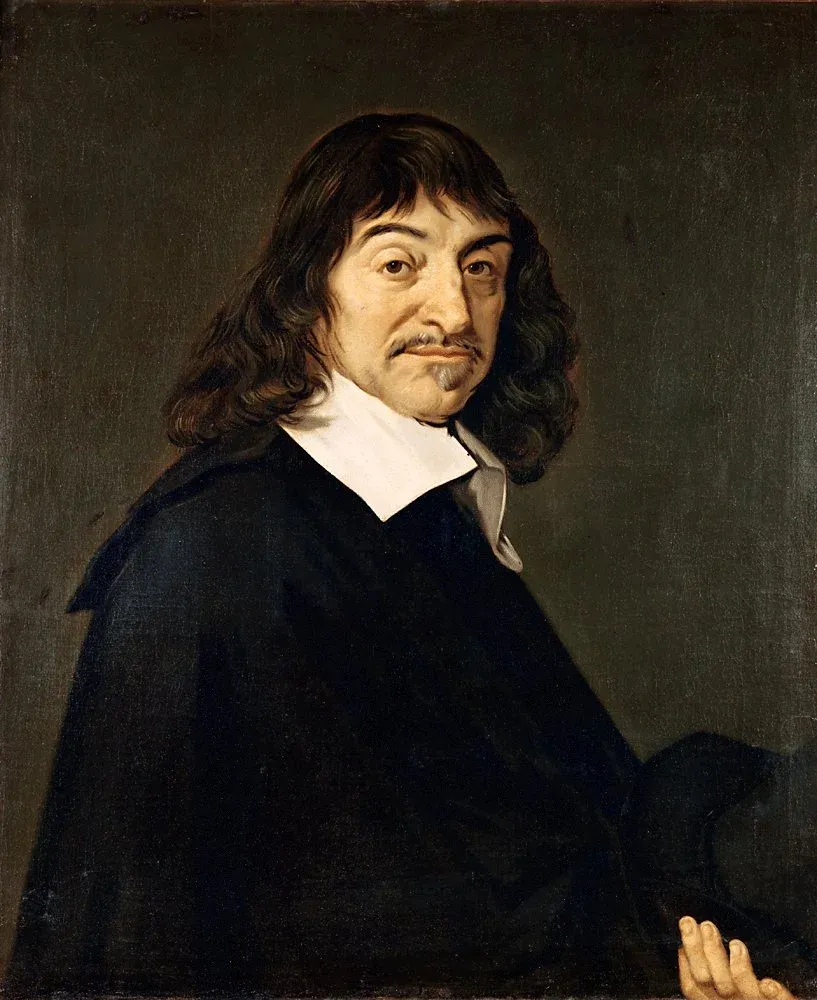

The more likely explanation is that René Descartes used the last letters of the alphabet to represent unknowns in his book “Discourse” (he used the first letters to represent constants). coordinate space is well known, and explains why we use and to represent a point on a plane. Some even claim Descartes chose the last letters because they weren’t common in French, hence the printer had many of them left over.

Amazingly well groomed for 1649

Amazingly well groomed for 1649

Now is one of the only ones on this list I am more certain about. Many theorize comes from the Greek word peripheria (περιφέρεια), but wouldn’t this mean ? Yes! Euler in fact defined as what we would today call , but he later redefined it to be . Why did Euler redefine it? We can only guess.

Sometimes I feel like this guy, and sometimes I feel like the Energizer bunny

Sometimes I feel like this guy, and sometimes I feel like the Energizer bunny

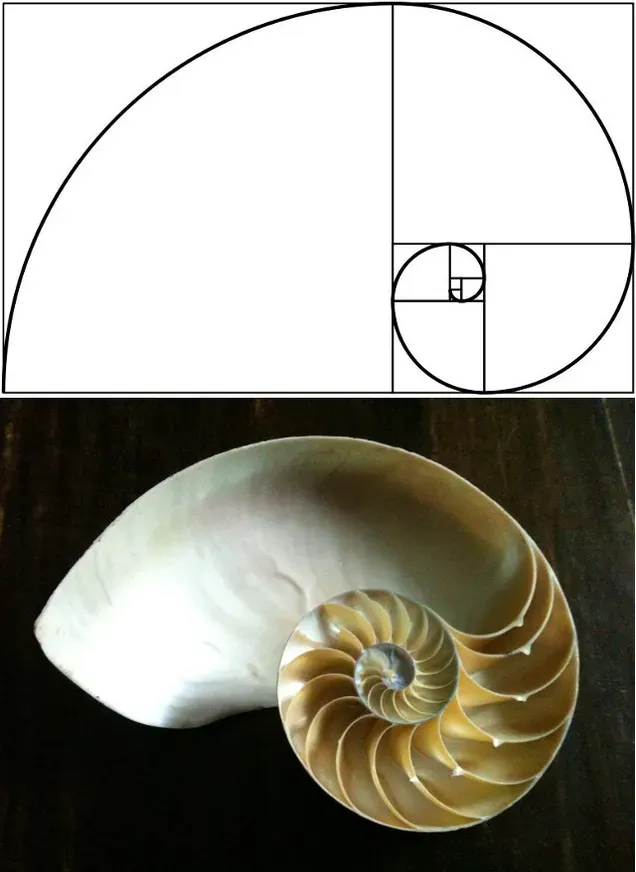

— the golden ratio — is a little harder to answer. The first time anyone used it was by Mark Barr in 1914. Phidias (Φειδίας), was a Greek sculpture, now recognized as one of the best of his time. Barr likely named the ratio after him, as Barr had thought Phidias used it in his work, even though he likely did not.

What’s your favorite example in nature?

What’s your favorite example in nature?

Conclusion

Well that was fun! Go off and do some research of your own next time you’re wondering where a symbol is from. Most of the time, no one has an answer, yet it’s still fun to go searching!

À bientôt,

Ilan Bernstein